How did we humans acquire our all-loving, unconditionally selfless moral conscience?

Written by Jeremy Griffith

This explanation is drawn from the Freedom Essay series on HumanCondition.com

Freedom Essay 20 explains how our species’ guilt over our present human-condition-afflicted angry and egocentric behaviour led us to contrive the excuse that we have ‘savage’ competitive, selfish and aggressive instincts, despite clear evidence that we humans actually have cooperative, selfless and loving moral instincts, the ‘voice’ or expression of which is our conscience. As Charles Darwin recognised, ‘The moral sense perhaps affords the best and highest distinction between man and the lower animals’ (The Descent of Man, 1871, ch.4).

And to have acquired our altruistic moral instinctive nature, it follows that our distant ancestors must have been cooperative, selfless and loving, not competitive, selfish and aggressive like other animals — which the following extracts from F. Essay 53 serve to illustrate (and you can find many more wonderful descriptions like these of our species’ past time in innocence in that essay).

- In 360 BC Plato, the greatest of all philosophers, wrote of ‘our state of innocence, before we had any experience of evils to come, when we were…simple and calm and happy…pure ourselves and not yet enshrined in that living tomb which we carry about, now that we are imprisoned’, a time when we lived a ‘blessed and spontaneous life…[where] neither was there any violence, or devouring of one another [no sex as humans practice it now], or war or quarrel among them…And they dwelt naked, and mostly in the open air…and they had no beds, but lay on soft couches of grass’ (see pars 158 & 170 of FREEDOM for source).

- In his poem Works and Days, Plato’s Greek compatriot Hesiod, some 400 years before Plato, wrote of our distant ancestors that ‘When gods alike and mortals rose to birth / A golden race the immortals formed on earth…Like gods they lived, with calm untroubled mind / Free from the toils and anguish of our kind…Strangers to ill, their lives in feasts flowed by…They with abundant goods ‘midst quiet lands / All willing shared the gathering of their hands’ (par. 180).

- The author Richard Heinberg states in his book, Memories & Visions of Paradise that all mythologies acknowledge a time of togetherness before the emergence of the human condition: ‘Every religion begins with the recognition that human consciousness has been separated from the divine Source, that a former sense of oneness…has been lost…everywhere in religion and myth there is an acknowledgment that we have departed from an original…innocence and can return to it only through the resolution of some profound inner discord’ (par. 181).

Bushmen of the Kalahari

- And finally, the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote that even with regard to some humans living today, ‘nothing is more gentle than man in his primitive state’ (par. 181).

The great biological question this leaves screaming out to be answered is, if all this evidence is true — that, as Darwin recognised, we have inherited altruistic, unconditionally selfless, cooperative and loving moral instincts from our distant ancestors, then how could our ancestors possibly have developed them? Since unconditionally selfless genetic traits are self-eliminating and therefore seemingly cannot develop in animals, then how could we humans have acquired them?

As explained in chapter 5 of FREEDOM, the answer was through nurturing (which, interestingly, Flaxman’s illustration for Hesiod’s Works and Days, included above, intimates).

While a mother’s maternal instinct to care for her offspring is selfish (as genetic traits normally have to be for them to reproduce and carry on into the next generation), from the infant’s perspective the maternalism has the appearance of being selfless. From the infant’s perspective, it is being treated unconditionally selflessly — the mother is giving her offspring food, warmth, shelter, support and protection for apparently nothing in return. So it follows that if the infant can remain in infancy for an extended period and be treated with a lot of seemingly altruistic love, it will be indoctrinated with that selfless love and grow up to behave accordingly — and over many generations that behaviour will become instinctive because genetic selection will inevitably follow and reinforce any development process occurring in a species; the difficulty was in getting the development of unconditional selflessness to occur in the first place, for once it was regularly occurring it would naturally become instinctive over time. And being semi-upright from living in trees, and thus having their arms free to hold a dependent infant, it was the primates who have been especially facilitated to support a prolonged and deeply connected mother infant relationship and so develop this nurtured, loving, cooperative nature. So it was through this ‘love-indoctrination’ process that our primate ancestors developed our moral conscience.

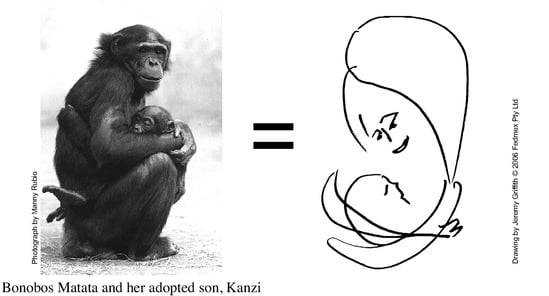

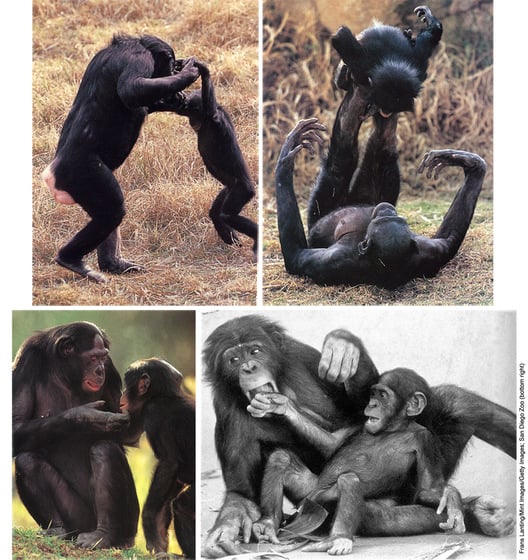

The bonobo variety of chimpanzees who live south of the Congo river are the most cooperative, selfless and loving of all non-human primates, and they are the most nurturing, as this quote evidences: ‘Bonobo life is centered around the offspring. Unlike what happens among chimpanzees, all members of the bonobo social group help with infant care and share food with infants. If you are a bonobo infant, you can do no wrong…Bonobo females and their infants form the core of the group’ (Sue Savage-Rumbaugh & Roger Lewin, Kanzi: The Ape at the Brink of the Human Mind, 1994, p.108 of 299).

These photographs illustrate just how nurturing bonobos are.

As to how cooperative, selfless and loving bonobos are, the following quotes (which are all referred to in chapter 5 of FREEDOM) provide powerful evidence. Firstly, from filmmakers who were producing a documentary about them: ‘they’re surely the most fascinating animals on the planet. They’re the closest animals to man [in that they share 99 percent of our genetic make-up]…Once I got hit on the head with a branch that had a bonobo on it. I sat down and the bonobo noticed I was in a difficult situation and came and took me by the hand and moved my hair back, like they do. So they live on compassion, and that’s really interesting to experience’ (accompanying film discussing the production of the French documentary Bonobos, 2011). And, as bonobo zoo keeper Barbara Bell said, ‘Adult bonobos demonstrate tremendous compassion for each other…For example, Kitty, the eldest female, is completely blind and hard of hearing. Sometimes she gets lost and confused. They’ll just pick her up and take her to where she needs to go’ (Chicago Tribune, 11 Jun. 1998). Bonobos’ unlimited capacity for love is also apparent in this wonderful first-hand account from bonobo researcher Vanessa Woods: ‘Bonobo love is like a laser beam. They stop. They stare at you as though they have been waiting their whole lives for you to walk into their jungle. And then they love you with such helpless abandon that you love them back. You have to love them back’ (The Guardian, 1 Oct. 2015). (You can watch some exquisite footage of the nurtured peace in bonobo society that was filmed during Jeremy’s 2014 visit with Professor Harry Prosen to the bonobos at the Milwaukee County Zoo.)

The consequences of this nurturing of unconditional love in bonobos is apparent in this quote: ‘bonobos historically have existed in a stable environment rich in sources of food…and unlike chimpanzees have developed a more cohesive social structure’ (Takayoshi Kano & Mbangi Mulavwa, ‘Feeding ecology of the pygmy chimpanzees (Pan paniscus)’; The Pygmy Chimpanzee, ed. Randall Susman, 1984, p.271 of 435). For example: ‘up to 100 bonobos at a time from several groups spend their night together. That would not be possible with chimpanzees because there would be brutal fighting between rival groups’ (Paul Raffaele, ‘Bonobos: The apes who make love, not war’, Last Tribes on Earth.com, 2003; see www.wtmsources.com/143).

Bonobo group

Note how the above photo equates perfectly with Plato’s description earlier of our ancestors (despite Plato having no knowledge of bonobos): ‘And they dwelt naked, and mostly in the open air…and they had no beds, but lay on soft couches of grass’. That evidences just how aware we are, if we are thinking honestly rather than evasively, of what life was like before the upset state of the human condition emerged!

It might be mentioned that (as explained in F. Essay 24 and chapter 7 of FREEDOM) another consequence of our ape ancestors having been nurtured with unconditional selflessness or love is that that orientation to love liberated the development of a fully conscious mind, which this further quote from Barbara Bell evidences is emerging in bonobos: ‘They’re extremely intelligent…They understand a couple of hundred words…It’s like being with 9 two and a half year olds all day’ and ‘They also love to tease me a lot…Like during training, if I were to ask for their left foot, they’ll give me their right, and laugh and laugh and laugh.’

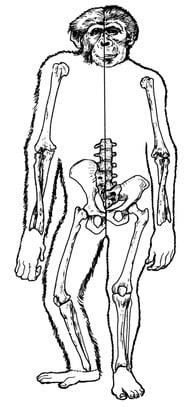

The drawing below illustrates how similar our ancestor was to bonobos — our ancestors are far more similar to bonobos with regard to their overall size, their bipedality, environment, lack of large canines, and lack of size differentiation between males and females, than any other existing primate — which indicates that our ancestors followed a similar path of development to the bonobos. So the evidence is that it was through the nurturing, love-indoctrination process that we acquired our altruistic moral nature.

Left side: Bonobo skeleton. Right side: Early australopithecine.

(Drawing by Adrienne L. Zihlman from New Scientist, 1984)

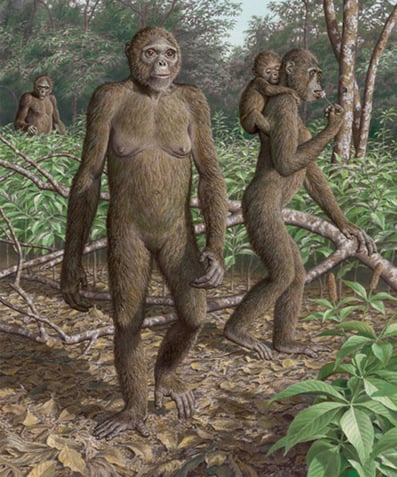

Indeed, the recent astonishing fossil discoveries, particularly those of the 4.5 million year old Ardipithecus that revealed these similarities between our ancestors and bonobos, have led the leading anthropologist C. Owen Lovejoy to acknowledge that ‘our species-defining cooperative mutualism can now be seen to extend well beyond the deepest Pliocene [well beyond 5.3 million years ago]’ (‘Reexamining Human Origins in Light of Ardipithecus ramidus’, Science, 2009, Vol.326, No.5949). (Much more can be read in F. Essay 22 about the insights being gleaned from the fossil record.)

Artist’s reconstruction of the 4.4 mya Ardipithecus ramidus in its natural habitat

(Painting by paleoartist Jay H. Matternes)

Although bonobos and the fossil record are only now revealing their corroborating evidence, in fact the nurturing, love-indoctrination explanation for our extraordinary unconditionally selfless, all-loving, social, moral instinctive self or soul is so obvious that only three years after Darwin tentatively ascribed the origin of our ‘social instinct’ to ‘parental’ ‘affections’ (The Descent of Man, 1871, ch.4), it was put forward as a developed theory by the philosopher John Fiske in his 1874 book, Outlines of Cosmic Philosophy: based on the Doctrine of Evolution.

-

Outlines of Cosmic Philosophy

-

John Fiske (1842-1901), about whom Charles Darwin wrote, ‘I never in my life read so lucid an expositor (and therefore thinker) as you are.’ (1874)

The outstanding question therefore is, why did Fiske’s nurturing explanation for the origins of our moral instincts — that was described at the time as being ‘far more important’ than ‘Darwin’s principle of natural selection’ (Dorothy Ross, G. Stanley Hall: The Psychologist as Prophet, 1972, p.262 of 482) and ‘one of the most beautiful contributions ever made to the Evolution of Man’ (John Drummond, The Ascent of Man, 1894, ch. ‘The Evolution of a Mother’) — virtually vanish from scientific discourse? (You can read much more about Fiske’s theory in chapter 6:3 of FREEDOM.)

The answer is that this nurturing explanation has been an unbearably confronting truth for parents trying to nurture their children adequately under the extreme duress of the human condition — a competitive, selfish and aggressive state that developed when humans became fully conscious after this time when we lived cooperatively and lovingly in the metaphorical ‘Garden of Eden’ state of original innocence. Our present insecurity about our inability to adequately nurture our children is painfully apparent in this quote from the bestselling children’s author, John Marsden: ‘The biggest crime you can commit in our society is to be a failure as a parent and people would rather admit to being an axe murderer than being a bad father or mother’ (Sunday Life, The Sun-Herald, 7 Jul. 2002).

It is ONLY NOW that we can explain the competitive, selfish and aggressive upset state of the human condition and thus understand why the present human-condition-afflicted human race hasn’t been able to adequately nurture our infants that it becomes safe to finally admit that nurturing is what made us human — that it was nurturing that gave us our moral soul and created humanity.

Again, this nurturing explanation of humans’ moral instincts is presented in full in chapter 5 of FREEDOM, while the biological explanation of why we became competitive, selfish and aggressive sufferers of the human condition when our conscious mind developed is the subject of Video/F. Essay 3, and fully explained in chapter 3 of FREEDOM.

Of course, if it was the emergence of consciousness that caused the human condition and our present inability to nurture, then there is another question screaming out to be answered: why did humans become conscious when other animals haven’t? A summary of the answer to this other great question in biology (which is a summary of the explanation in chapter 7 of FREEDOM) is presented in F. Essay 24.

Before reading the essay on consciousness we recommend reading F. Essay 22: Fossil discoveries evidence our nurtured origins; then an essay explaining that there is an integrative direction, purpose and meaning to existence (F. Essay 23). The reason for the inclusion of the Integrative Meaning essay before explaining how we became conscious is because an appreciation of the integrative meaning of existence is needed if we are to understand how we became conscious.

The Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania’s Serengeti Plains has yielded a series of important fossil remains of early humans

The Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania’s Serengeti Plains has yielded a series of important fossil remains of early humans